Steven Theriault believes he has a solution to the urgent global public health threat – antibiotic resistance.

But it can’t get its bacteria-killing virus approved under Canada’s rigid and outdated regulatory system.

“The next big focus in science is really on genetics and living organisms. (…) I think we’re going to create some really exciting treatments and technologies,” he told CBC News during a recent tour of his lab.

“I hope in the future that the Government of Canada…changes the regulatory process because this really is something that will save lives in Canada and also improve the treatment of our cattle herds in Canada. And now we can’t. Use this.” I can do it.”

Theriault is a former paramedic who earned a PhD in molecular genetics and virology and then spent 15 years working on projects such as the Ebola vaccine at Canada’s only Level 4 national microbiology laboratory in Winnipeg. He left in 2018 to start his own biotech company, Cytophage.

His research involves phages – or bacterial viruses – that work by attaching to bacteria and injecting them with genetic information, replicating until they are free from the bacteria. It seeks out other hosts to kill.

Steven Theriault has a model of phages, which are bacterial viruses that work by attaching to bacteria and internalizing their genetic information, until the bacteria themselves are expelled.

Steven Theriault has a model of a phage, a bacterial virus that works by attaching to a bacterium and internalizing its genetic information until the bacterium itself is expelled, building more, looking for more hosts to kill. (Gary Soleilac/CBC)

Phages were discovered in 1915 and used to treat cholera during the 1927 epidemic, but were overshadowed by the rise of antibiotics in the 1940s. That is, until antibiotic-resistant bacteria emerge.

The problem is that they are highly targeted – the individual stages are very specific to their hosts. That’s where Theriault and his team come in: They can modify and genetically engineer phages that attack a range of bacteria.

While this may sound intimidating, Theriault says there is no known way to detect the gain of function that would enable bacteriophages to cause disease in humans.

“It can only be used against bacteria; It cannot be used against people,” he said. “It doesn’t infect human cells, it doesn’t infect animal cells. And you probably have about 100 trillion of them right now.”

Theriault believes bacteriophages are the answer to antibiotic resistance, which according to the World Health Organization (WHO) is one of the greatest threats to health, food security and development in the world, linked to almost five million deaths in 2019.

The era of drug-resistant pathogens

He’s not the only one who believes this. The University of Toronto, California at San Diego and the USA Research from places such as the National Institutes of Health suggests that “phage therapy has the potential to be used as an alternative or complement to antibiotic therapy” and may provide an alternative to antibiotics. The era of drug-resistant pathogens.

Can phage therapy help fight antimicrobial resistance?

The main cause of this resistance is the overuse of antibiotics in humans and animals, which kill some bacteria but allow others to mutate and develop defense systems. A growing number of infections, including pneumonia, tuberculosis, gonorrhea and salmonella, are becoming harder to treat as antibiotics are less effective against resistant superbugs.

About 70 percent of antibiotics worldwide are used in animals. Until recent regulatory changes, Canadian producers administered antibiotics to livestock and poultry as a preventive measure. The side effect was that it helped them gain weight, but it also seeped into the groundwater and left traces in the meat, causing antibiotic-resistant bacteria to grow in the animals and humans who ate them.

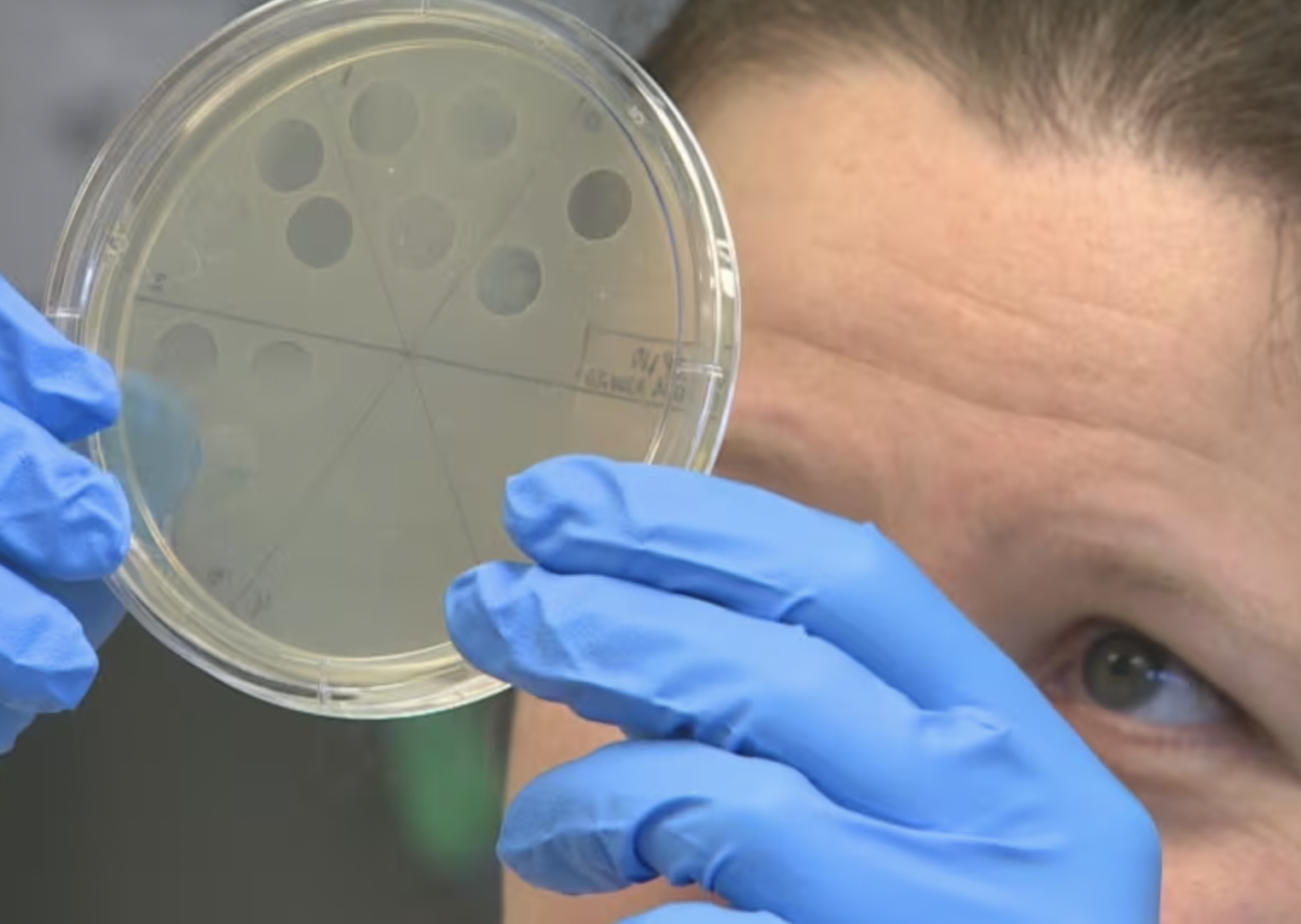

Cytophage scientist Tasia lightly looks at the places where Pharmphage killed what????

Research associate Tasia Lightly examines a petri dish where phages can be seen clearing areas where bacteria have been killed. (Gary Soleilac/CBC)

Theriault and his team started working on the problem of human immunity, but soon expanded their work to agriculture.

They developed and tested a product called Pharmphage, a cocktail of bacteriophages that kills E. coli and Salmonella in chickens. In a study conducted by the University of Saskatchewan’s Institute of Vaccines and Infectious Diseases, the survival rate for chickens infected with E. coli was 92 per cent, compared with eight per cent for untreated birds.

Research conducted in Bangladesh showed that after administration of pharmphage, the protein content of chickens increased by 22 percent, the amount of food needed for growth was reduced by 12 percent, and the chickens achieved full production two days earlier. and weight. achieved

Theriault says the birds are also healthy. When flu broke out in their barns, chickens in Bangladesh who received Pharmphage survived better than chickens in control barns.

Consent is being obtained in America

They believe their product could also be adapted to treat people suffering from infections caused by drug-resistant superbugs.

During a field trial conducted in Bangladesh in May 2023, Farmface was added to the water of newborn chicks. The product demonstration was organized in cooperation with Renata Limited, a local pharmaceutical and animal health products company.

PharmPhase was added to the water of newborn chicks in a field study conducted in Bangladesh in May 2023. (Tacia Lightly/Cytophage). Theriault Pharmaphase has been submitted for approval in the US and is expected to start sales in that market in 2024. It is also looking at the European Union and Australia, which are developing regulatory frameworks for use in those countries.